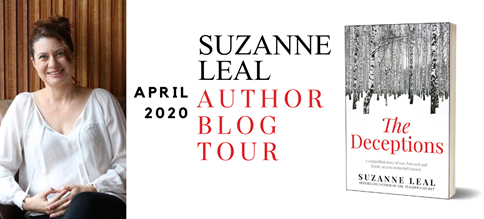

In these awkward days, I feel it’s important to have something to read to take us away from news and endless refreshing. I’m pleased to share with you today a chapter sampler from The Deceptions by Suzanne Leal. It’s a story across time full of secrets and intrigue:

Moving from wartime Europe to modern day Australia, The Deceptions is a powerful story of old transgressions, unexpected revelations and the legacy of lives built on lies and deceit.

Prague, 1943. Taken from her home in Prague, Hana Lederova finds herself imprisoned in the Jewish ghetto of Theresienstadt, where she is forced to endure appalling deprivation and the imminent threat of transportation to the east. When she attracts the attention of the Czech gendarme who becomes her guard, Hana reluctantly accepts his advances, hoping for the protection she so desperately needs.

Sydney, 2010. Manipulated into a liaison with her married boss, Tessa knows she needs to end it, but how? Tessa’s grandmother, Irena, also has something to hide. Harkening back to the Second World War, hers is a carefully kept secret that, if revealed, would send shockwaves well beyond her own fractured family.

Inspired by a true story of wartime betrayal, The Deceptions is a searing, compassionate tale of love and duplicity-and family secrets better left buried.

Enjoy the first chapter below!

PART 1

HANA

My husband is dead, dead a year now—dead since the fourteenth of March 2009—so I lit him a candle. Then I let it burn. Because that’s what you do with a Yahrzeit candle: you let it burn and burn until finally it burns itself out.

Not that mine was a real Yahrzeit candle. Mine was simply a long-burning candle from the new gift store in Dorchester. It won’t last. The gift store, I mean, filled as it is with overpriced knick-knacks, my faux-Yahrzeit candle included.

It was the first time I had left a candle to burn all night. As a child I had witnessed my mother do it. Every year she would light a candle on the anniversary of my grandmother’s death. She would light it in the evening and she would leave it while we slept. And never once did the house burn down. It never even crossed my mind that it might. Then I had absolute confidence in the way of the world. Then I knew for certain that, each year, our Yahrzeit candle would simply burn all night and all day and then it would stop.

Afterwards, when everything around me had burnt away and everyone I had known was gone, I did not light a candle. Not for any of them. I had people to mourn, that was true enough, but I didn‘t know when, exactly, they had died. And if I did not know that, how could I light a Yahrzeit candle on the anniversary of their passing?

Instead I determined to leave it all behind me. All the dead, all the misery, all the loss. I would make of myself something new, someone new.

As luck would have it, my husband came at exactly the time I needed him, bringing with him the disguise I required to become the woman I was not.

But now he is gone. One year gone and still the sadness lingers. That has surprised me. In this long life of mine, there has been sadness such that it might have engulfed me had I let it. But I never did. I never let the sadness smother me. So, why can I not shake it now? Why will it not leave me now?

The answer comes in the small hours of the night, the candle burning beside me. With my husband gone, I no longer have the strength to resist that push inside me, that urgent press from the girl who had once been me, and who was calling once again to be seen.

*

Hana is the name my parents gave me. The Germans added Sara. Lederova was mine by birth.

Afterwards, I got rid of them. The whole lot. I discarded all those names and I started again.

My husband handed me a new surname. The given name I came to myself. And in this way, I disappeared. In this way, Hana Lederova—Hana Sara Lederova—was no more. And I was happy about that.

When I was still Hana, I lived most of my life in Prague. It was a life of good fortune and I was a fortunate girl, even if I didn’t know it at the time.

Let me tell you a little of this fortunate girl, this girl who was once Hana Lederova. She was attractive, appealing. Some might even have called her compelling. But few would have described her as a great beauty: her eyes, noteworthy for their colour—honey brown with flecks of green—were too deeply set, and on the right cheek, her skin was marred by a distinctive mole. Her hair, dark with glints of auburn, was worn long, in defiance of the fashion, and those who hankered for sleek,

glossy hair would have been disappointed by the unruliness of the abundant curls.

Now, as I run my comb through hair that is no longer dark, that is no longer thick, I envy this girl with everything except conventional beauty.

I was the only child of parents who doted on me. By the time I announced my appearance, my mother was almost forty and had despaired of ever having a child. And her delight when finally I arrived was, I am told, beyond measure.

My father was a dentist. Dentists are never loved the way doctors are loved but perhaps they should be: many were the patients who presented to my father in agony, only to leave the surgery if not with a smile on their face, then at least with

relief in their eyes. For his patients, my father would always make himself available. For my mother and me, he was everything.

Without descending to sycophancy—I have never been a fan of this—my father was an exceptional man, an exceptional person. Dentistry was his vocation but music was his great love. And so I was raised to be musical. And musical I was.

My mother appreciated my playing and also my singing: it was a gift, she told me. Sometimes she told this to other people, too. She herself did not play the piano, did not sing. Her parents were serious and business minded, with no interest in music. They were solid, wealthy, unremarkable people who had somehow produced my mother, who was so beautiful she astonished people. For a woman she was tall. She was also slender. Not boyish but almost. In this regard, I did not take after her. I was lean, yes, but buxom where she was small, my waist pronounced where hers was not. My mother’s beauty was an exotic combination that puzzled her family: her eyes were dark and the shape of almonds, her skin very pale and her hair, which she kept closely cropped, was dark and shiny. She had that particular confidence some call arrogance. It was from my mother I learned how to hold myself. ‘If you stand tall,’ she would tell me, ‘people will think you confident. And if people think you confident, they will believe that there is a reason for it. And whatever they believe that reason to be—intelligence, wit, beauty—they will think you have it. Simply by the way you stand.’

Throughout my life, this is exactly how it has been. I have stood tall, even when I felt small and frightened. Even when all of my confidence was gone, still I stood tall. And now, when my contemporaries hunch over in a stereotype of the ageing process, still I stand tall. I am proud of this. And why not? I have reached an age where there is less to look forward to, fewer markers of success. So, why not be proud of standing straight? Surely I shouldn’t be denied this opportunity.

Ha! Listen to me, with my whining, my declaration of the right to stand tall. Then again, why not, in a world obsessed by a right for this and a right for that?

Such a nonsense, but so you have it.

Physically, my parents were an odd match: my mother so tall and dark and willowy, my father—well, let’s not search for better words—squat and thickset and plain. But clever and loving and doting.

My father’s dental surgery was attached to the front of our white, thick-walled house but not accessible to it. Instead, there was one entrance to the surgery and a separate entrance to our house. While my father administered to his patients—at all hours of the day—my mother managed the surgery: she was receptionist, office manager and, when required, dental assistant, too. Meanwhile, I was raised by my nanny, Ada. Ada was cheery and energetic and kind and she ran our household—first as nanny, and then when I was too old for that, as housekeeper—until we were ejected from the house. And the surgery. Until we were forced to leave everything. Even Ada.

What happened to her? I don’t know. I never found out. Nothing much, in all probability. For she was not Jewish. She was not like us.

Jewish? Yes. Jewish. Well, yes and no. For Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur you might find our family in the synagogue. Never more regularly than that. And we ate whatever we liked. On New Year’s Eve we had pork and lentils for good luck. My father was partial to shellfish. It would be a mistake to say we kept kosher.

All of this to say one thing: Yes, we were Jewish, and no, we were not Jewish. We were Czech, simply Czech.

But only until 1939. Yes, yes, yes. Everyone knows the significance of the year. Or perhaps not everyone. Perhaps not the young ones for whom this is now too far away to contemplate. 1939. The year after we were thrown to the wolves, the year after that apologist Chamberlain decided the Czechs were expendable and that Hitler was welcome to our land, our Sudetenland.

So, yes, first the Sudetenland was gone: off to Germany, off to the Third Reich. A bone to throw to that madman. But madmen are so hard to satisfy, aren’t they? And Herr Hitler was not only a madman, he was also clever. So much better to have a madman who is stupid. Not Hitler. Not him. So, thank you, Mr Chamberlain, for your appeasement of the madman, which was no appeasement at all. Which simply opened the door to the remainder of our small country. And when, sure enough, Hitler

and his men took over all of it, what did we do? With the rest of the world, we looked on. I did, too, I admit it. I didn’t scream and yell and throw myself under the tanks that rolled into Prague. Rolled in on the wrong side of the road, I might add. German skill at its best: invade the country and change the direction of its traffic, all in one move. In a bloated Third Reich, there was no place for left-hand traffic. Conformity is the enemy of dissidence, and the friend of efficiency. And the Germans have always been an efficient bunch, haven’t they?

But hush with this. Hush. For though the Nazis were German, the Germans were not necessarily Nazis. So, they should not be lumped together. Although I confess that sometimes I still do, even now. When, for example, I see a German car, still I have to fight the urge to grab something sharp, a knife or a screwdriver, so I can scratch down the side, the front, the back of it: no matter the brand, no matter whether it is a Mercedes-Benz, an Audi, a BMW or that ludicrously named people’s car, the Volkswagen.

Enough.

Enough.

Thoughts like these still trouble me, leave me disturbed. Breathe, breathe—for where does the anger get me? Nowhere. That is my mantra to myself: Anger gets me nowhere. Although if I am honest—and I am mostly honest—sometimes I still have a

need to feel the fire of it. With the arrival of the Germans, I became a Jewish girl who happened to live in Czechoslovakia rather than a Czech girl who happened to be Jewish. Every day, it seemed, there were more rules for a Jew like me. First came the curfew, then the headcount, then the confiscation of our radios, then we were banned from leaving the country.

Earlier, much earlier, my mother had agitated to get us out, to flee to Britain. My father had some English—even if she did not—and his skills as a dentist would surely have been valued. But my father wouldn’t countenance it.

The madness will not last. This was my father’s catchcry. For years he had been saying it, would continue to say it: The madness cannot last.

In the end, he was right, wasn’t he? The madness did not last and the madman did not last. He saw to that himself. A gun in his mouth, or was it to his head? And that was that. Only a decade too late.

Yes, I sound matter of fact. Yes, I sound callous. I know that. But even now this is how I must behave. For were I to unleash myself, were I to give voice to the horror, the anger, the fury still inside me, I would completely lose control.

Instead I try to breathe. I breathe in, I breathe out. This is the way I calm myself. When I think about my father—who could have listened, who should have listened—I breathe in and I breathe out. And I try to accept what is done, that nothing can be changed and no one can be brought back. Yes, I try to accept this, for as everyone tells me, if there is a peace to be found, this is how I shall find it.

But that is a noble endeavour and I cannot always manage it. For sometimes a flicker of rage will rise in me. Not untethered rage, not rage that flails and thrashes. Not that. Just a flicker. A flicker I try to manage so it will not ignite me, will not consume me. But that is not always so easy.

I love the sound of this book.